Like we discussed in the most recent blog (HERE), periodization is the breaking up of long term training goals into smaller, more manageable blocks with specific targets. Within each block, we manipulate the main training variables - volume and intensity - to best suit our performance goals. There are several different paradigms for periodized training. Let’s dive in…

Linear periodization is the model that involves systematic and consistent changes to volume and intensity over time. In the traditional model, intensity starts low and volume starts high. Over time, these two swap places. See the first chart below:

Over the course of the training cycle, the intensity (which started low) increases while the volume decreases.

Over the course of the training cycle, the intensity (which started low) increases while the volume decreases.

In the reverse linear model, the opposite occurs. Intensity starts off high but will progressively decrease while the volume starts low but increases throughout the training cycle.

Linear models have several issues, one of which is the constant upward adjustment of at least one training variable, which can lead to excess fatigue. In addition, these models assume preparation for a single event or competition. This can work for events such as a single marathon or other competition. On the other hand, how do you avoid potential injury due to over use or over training, particularly if you are participating in multiple events throughout a season as most athletes do? Enter the undulating, non-linear model…

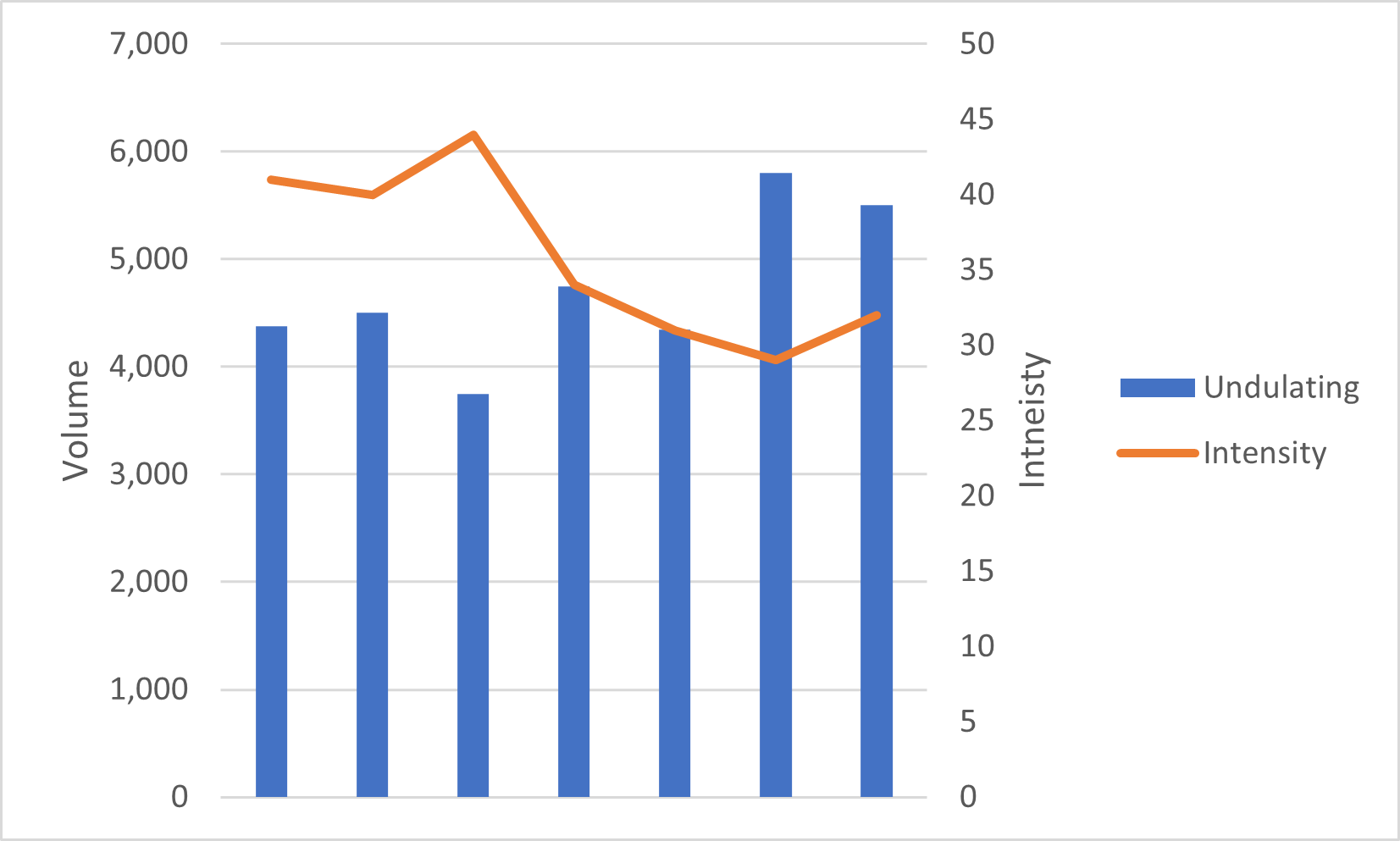

In this model, volume and intensity are changed seemingly at random (but actually on not). The only constant is change! This method actually has a few interesting considerations, the first of which is the decreased risk of injury. The occasional down periods allow for increased recovery. The second, more interesting consideration (although being injury-free is pretty nice) is that the constantly changing load might serve as a more effective stimulus to growth than repetitive or consistent changes to load. Think of it as keeping your body and muscles off balance. When there’s a new stimulus (say, much higher volume in one particular micro cycle), your body has to scramble even more to adapt.

Lastly, for advanced athletes, another form of periodization called block (or sometimes conjugated) periodization is often used. In this model, several micro cycles are used to focus on specific performance abilities while other abilities are kept at consistent loads. For example, let’s say you are a distance runner who is training for a marathon but has several 5K races along the way. Because the marathon is such a long event, you must keep your training volume high but since the 5K is a shorter run with more of a speed focus, you want to add some track workouts to your weekly regimen. Your total training output might look like this:

Here, notice how the training volume stays relatively consistent, but the intensity increases over time as you add more speed running to the plan. Keep in mind, this is an advanced form of training and the overall load is quite high.

We discussed four different models for structuring a training plan. Whichever one you choose to follow will depend on your current training goals but keep it mind, training by itself follows an undulating course over the long haul. No training plan is up and up and up. Remember to have off-loading or recovery cycles to prevent burn out but more importantly, injury.

Train hard!

Works Cited:

Baechle, T.R., Earle, R.W. Essentials of Strength and Conditioning. Third Edition. Human Kinetics. 2008.

Kramer, S. Be Fit to Ski: A Complete Guide to Alpine Skiing Fitness. Xlibris, 2015.

Kenney et al. Physiology of Sport and Exercise. Seventh Edition. Human Kinetics, 2020.